Prologue

In an article Pentagram Advisory published in January 2025, titled The Insider Threat and AUKUS: Safeguarding Australia’s Strategic Partnership we considered the incoming Trump administration’s concern with insider threat within the United States Government, the military, and defence sector.

By extension, in the article, we explored what such concerns within Trump’s administration might herald for Australia in terms of expectations of Australia’s performance as an ally. Particular focus was given to the personnel security expectations Australia has signed up for as a first-tier military and intelligence ally. Further, we examined Australia’s role as a planned custodian of some of the most sensitive U.S. military technology secrets, as manifest in AUKUS, especially in the Pillar 1 nuclear submarine program.

In the weeks since Pentagram published that article, I have seen President Trump’s administration enact sweeping and extraordinary changes, albeit by Presidential executive orders rather than legislation through Congress. This approach has allowed President Trump to reshape the U.S. government, finance, aid, society, military, intelligence, alliance, and other components of government and statecraft at unprecedented breakneck speed. Trump’s approach is testing the limits of presidential power and upending norms that have been in place for generations. Some political commentators have said Trump’s approach is ‘revolutionary’.

Amongst Trump’s changes is dismantling the Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) programs and associated funding put in place by the Biden administration and many of its predecessors. Aligned to this dismantling of the DEI edifice is the U.S. Supreme Court ruling from June 2023 which found race-conscious affirmative action for admission of students into colleges violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Trump’s focus on dismantling DEI plays out in the context of the ‘real world’, where everyday people in the U.S., Australia and many other countries are subject to pressures and drivers from both very anti-DEI behaviours and highly pro-DEI behaviours, reflecting racial, religious, social, economic, and geopolitical frictions. These behaviours reflect reality.

With the points above in mind I offer two observations to conclude this introduction. What happens in the U.S. domestically and what the U.S. does internationally have significant global resonance and, often, significant consequence. Further, none of these drivers spanning racial, religious, social, economic, and geopolitical frictions are going to dissipate any time soon. The times we live in are volatile and uncertain. And if you doubt the veracity of the U.S. DEI influence on Australia, then consider how the 2020 Black Lives Matters (BLM) movement in the U.S. resonated here in Australia.

With this context in mind, in this article, I will delve deeper into the issue of insider threat in the Australian context of today. It is important to examine insider threat, to flag the significance of insider threat to critical infrastructure and defence industry entities and to any private and public sector entity. If an entity has a workforce, then the entity is subject to some form of insider threat.

What is Australia doing about insider threat?

There has always been an awareness of insider threat in sectors of the economy including finance, gaming, taxation, government, infrastructure, aviation, defence, banking, intelligence, law enforcement and more.

An insider threat is defined as a person who uses their legitimate access to an entity’s assets and information to cause harm to that entity. The insider could cause harm intentionally or unintentionally, but the consequence (harm) may well be the same.

The insider has long been a recognised threat in Australia’s Defence, national security, and intelligence agencies with significant personnel security effort devoted to mitigation.

So, how has Australia viewed the insider threat in recent years?

In November 2021, the Commonwealth’s Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) Policy 12: Eligibility and suitability of personnel and its Policy 13: Ongoing assessment of personnel were amended to give effect to the TOP SECRET-Privileged Access (or TS-PA) Standard. An insider threat program, including ongoing monitoring of people with TS-PA clearances, is an artefact of a TS-PA security regime. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) manages the TS-PA capability.

However, only in late 2023, many Commonwealth departments outside the national security community were directed to establish an insider threat program. This requirement was clarified in November 2024 amendments to the Commonwealth’s PSPF which most Commonwealth departments are subject to. The amendment, known as Requirement 51, states: “An insider threat program is implemented by entities that manage BASELINE to PV security clearance subjects to mitigate the risk of insider threat in the entity.” This means if any person within an entity holds a Commonwealth security clearance at any level, then an insider threat program is required by the sponsoring entity. Note that individuals with BASELINE to TS-PV clearances are vetted on a ‘point-in-time’ basis, are required to self-report, and their suitability may not be security reviewed in any meaningful way for years.

Also, in 2023 it became clear that critical infrastructure entities, most of which are private sector entities, have obligations under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SOCI Act) requiring them to mitigate insider threats for both their ‘critical workers’, broader workforce, and into their supply chain. Whilst the SOCI legislation does not explicitly use the term ‘insider threat program’, such a program is the mechanism required to manage insider threat across a critical infrastructure entity, as expressed in the SOCI legislation.

Further, Australia’s partners in the AUKUS enterprise, the United States and the United Kingdom, have decided to maintain and construct nuclear-powered submarines in Australia and share select secret advanced technologies and research with Australia. This arrangement will require the creation and operation of robust insider threat programs, aligned with U.S. and UK security practices, capturing tens of thousands of people across Australia and overseas. Australia cannot afford to fail to safeguard the nuclear technology secrets and submarine operations information that our key allies are willing to share. Insider threat programs for key government, defence, and private sector AUKUS entities are in place and will need to grow. These will be complex and demanding to operate effectively.

To summarise, we have seen in Australia over the last four years that ASIO, the Department of Home Affairs (responsible for PSPF and SOCI) and the Department of Defence (AUKUS) new demands for insider threat programs making clear the serious risk posed to Australia’s national security by insider threats.

The insider threat program requirement applies to both public and for private sector entities. Government entities have a history of managing insider threats, it is embedded in their culture, whereas most private sector entities do have this cultural DNA.

Is insider threat real in Australia today?

In late 2024, Australia’s Commonwealth Counter-Terrorism Coordinator, Nathan Smyth, posted a video in which he stated:

“In August [2024], the Director-General of Security raised the National Terrorism Threat Level back to ‘PROBABLE’, reflecting the complex social, political, and security environment we are currently facing.

The threat of terrorism and violent extremism is dynamic and constantly evolving.

We are witnessing an increase in anti-government and anti-authority violent extremism, and the use of emerging technologies to enable, produce, disseminate, and amplify messages of hate and violence.

We must remain alert and be responsive to this ever-evolving security landscape.

Australia’s Counter-Terrorism and Violent Extremism Strategy marshals the strength of the Australian community to reinforce our national resilience and reduce current and future threats posed by terrorism and violent extremism.

The Strategy is for all Australians to develop a greater understanding of the evolving threat and what Australian governments are doing to respond to these challenges.”

It is important to register that Commonwealth Counter-Terrorism Coordinator Smyth stated that dealing with an increase in anti-government and anti-authority violent extremism is not the Commonwealth’s challenge alone. Smyth emphasised that reducing threats posed by terrorism and violent extremism will require the entire Australian community. I see that as a clarion call on the private sector to play its part.

Aligned with Smyth’s statement is corresponding policy titled A Safer Australia: Australia’s Counter – Terrorism and Violent Extremism Strategy 2025 which states:

“A growing number of Australian are being radicalised to violence, and radicalised to violence more quickly. More Australians are embracing a diverse range of extreme ideologies and a willingness to use violence to advance their cause. We are witnessing an increase in anti-government and anti-authority violent extremism, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia, and the use of emerging technologies to enable, produce, disseminate and amplify messages of hate and violence at an unprecedented scale and pace.”

“Australia must be responsive to an ever-evolving security landscape. Effective prevention is our best defence. As a first step this means building capacity within our communities to guard against the threat of violent extremism. A second critical step focuses on early identification, intervention, and diversion of individuals on the path to violence who are motivated by extremist ideologies. This requires bolstering support to young people at risk, and strengthening partnerships between government, communities, academia, and industry.”

On 19 February 2025, the Director-General ASIO in his Annual Threat Assessment said:

“Australia has entered a period of strategic surprise and security fragility.

Over the next five years, a complex, challenging and changing security environment will become more dynamic, more diverse and more degraded.

Many of the foundations that have underpinned Australia’s security, prosperity and democracy are being tested: social cohesion is eroding, trust in institutions is declining, intolerance is growing, even truth itself is being undermined by conspiracy, mis- and disinformation.

Similar trends are playing out across the Western world.

So what does this mean for our security environment?

Australia is facing multifaceted, merging, intersecting, concurrent and cascading threats. Major geopolitical, economic, social and security challenges of the 1930s, 70s and 90s have converged. As one of my analysts put it with an uncharacteristic nod to popular culture: everything, everywhere all at once.

Australia has never faced so many different threats at scale at once.”

To illustrate how real the risk of insider threat is in Australia we can cite reporting in the Australian media on 13-14 February 2025.

Two nurses employed in the state government entity NSW Health, at Bankstown Hospital, listed as a critical hospital under the Security of Critical Infrastructure (Critical infrastructure risk management program) Rules 2023, reportedly engaged in an online chat forum with an Israeli person and were recorded on video as saying they would kill any Israeli patient they might be required to give medical assistance to as part of their employment as nurses at Bankstown Hospital.

One of the nurses, Ahmad Nadir, reportedly told the Israeli person in the chat that he “had no idea” how many Israelis who had attended Bankstown Hospital he had sent to “hell”.

The other nurse in the chat, Abu Lebdeh, reportedly said she would not treat Israeli patients but would “kill them”. Lebdeh reportedly went on to say that Israel is Palestine’s country, not your (Israel’s) country.

NSW Health stood down both nurses immediately once the chat video was made public. The police are gathering evidence to ascertain if charges might be laid.

This is an insider threat case in Australia in February 2025, and it has garnered international headlines.

These nurses were employed by NSW Health and presumably showed no signs of violent tendencies or, hopefully, of overt anti-Semitism or a willingness to kill patients during the employment screening process. It is likely that the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, and the ensuing war in the Middle East, triggered within Lebdah and Nadir latent behavioural norms and attitudes that they had been exposed to historically (Nadir fled Afghanistan as a 12-year-old and became an Australian citizen in about 2020) and in contemporary Australia, perhaps within their community, as part of the wave of anti-Israeli sentiment and violence that has swept the globe, and especially Western democracies, in the wake of the 7 October attack. Mainstream media, social media, and chat forums have been fundamental in spreading an anti-Israel view.

My comments about an external event ‘triggering’ Lebdah’s and Nadir’s behaviour aligned with comments made by DG ASIO on 19 February 2025 when he said in his Annual Threat Assessment:

“Anti-Semitism festered in Australia before the tragic events in the Middle East, but the drawn-out conflict gave it oxygen – and gave some anti-Semites an excuse.

Jewish Australians were also increasingly conflated with the state of Israel, leading to an increase in anti-Semitic incidents.

The normalisation of violent protest and intimidating behaviour lowered the threshold for provocative and potentially violent acts. Narratives originally centred on “freeing Palestine” expanded to include incitements to “kill the Jews”. Threats transitioned from harassment and intimidation to specific targeting of Jewish communities, places of worship and prominent figures.”

How might an insider threat program help mitigate such risks?

The starting premiss of an insider threat program is to identify aberrant behaviour – the program does not target the person. However, as the Counter-Terrorism Coordinator says: “We must remain alert and be responsive to this ever-evolving security landscape.”

To that end, an effective insider threat program would have assessed that the rise in anti-Isreal and associated anti-Jewish sentiment in Australia may result in some employees undergoing change to the attitudes and behaviours they bring to the workplace, perhaps being adversely affected such that their workplace behaviour may evolve into a harm in the workplace and perhaps also to themselves.

Reporting indicates that Nadir and Lebdah are Muslim and may have been susceptible to evolving attitudes and behaviours inimical to the requirements of NSW Health and Bankstown Hospital. An insider threat program may have recognised Muslim employees could be adversely affected and taken steps to mitigate such a risk, preferably by early engagement intended to prevent such a situation developing, but failing that, to monitor vulnerable employee’s attitudes and behaviours to stop them from committing harm.

Nadir and Lebdah’s reported behaviour shows that harm was realised, and whilst NSW Health on 12 February 2025 stated there is no evidence that any Israeli has been harmed or killed at Bankstown Hospital (with investigation ongoing), this insider threat event has inflicted serious harm on the confidence people have in the public health system which is a pillar of Australian society. Of course, if there are medical professionals in Bankstown with this homicidal view then it stands to reason there could be others across Australia’s health system holding similar views. This insider threat act has resonance across all of Australia and also internationally.

There is reporting that an employee at Bankstown Hospital reported instances of colleagues (not named in media reporting) chanting anti-Israel slogans and wearing pro-Palestinian clothing, with images posted on the hospital’s website, in the wake of the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel. It appears that the reports did not trigger an investigation by Bankstown Hospital management, though the employee who reported the instances apparently received a form of caution for lodging such a report.

An insider threat program would encourage such employee reports because the behaviour could be an indicator of a potential insider threat and so would warrant serious consideration and, potentially, investigation.

Let’s extrapolate that point to show the value of an insider threat program. What if the employee report from 2023 had identified the behaviour of a person who was subsequently investigated and found to have attitudes that would support harming an Israeli (Jewish) patient? Intervention at that point could have resulted in the employee being supported by the hospital, reining back their violent views, and remaining at work with a supportive package.

Or, what if the employee was not assessed and went on to harm a patient? Aside from the harm to the patient, the employee would have self-harmed, and the reputation of Bankstown Hospital and NSW Health could have been severely damaged. Healthcare professionals would have been mortified and harmed themselves by such an event.

This Bankstown Hospital case brings perhaps the most significant component of managing insider threat to the fore, and that is ‘trust’. When a person is admitted into a group or employed there is both an implicit and explicit granting of trust to the newcomer.

Turning to research about trust, a long-term study[1] investigating people’s neurological responses to ‘trust’ concluded that building a culture of trust is what makes a meaningful difference to individuals’ relationship with work and hence to the enterprise they are part of.

The research indicates that people in ‘high-trust’ enterprises are more productive, have more energy at work, collaborate better with colleagues, and stay with their employers longer. This high trust environment meets their needs as a person. The study offers eight management behaviours that can foster employee trust. It suggests that leaders and managers are the fundamental enabler to grow trust: leaders must provide the conditions for success – clear direction and suitable resources – then allow people to get on with the task, supervised (coached) but not micromanaged.

I contend that a person is less likely to become an insider threat to an enterprise that offers them a culture of trust within which they are emotionally rewarded and socially enriched.

This study shows that trust is a core component of a secure workplace and so when a trusted insider acts to cause a harm then one of the consequences is damaged trust within the workplace and diminished trust by stakeholders in that entity so reputation is damaged. In the case of the Bankstown nurses, trust in the essential health services vested in Bankstown Hospital, and by extension NSW Health and Australia’s public health system, has been harmed. This example shows the potency of the insider threat – one person can cause significant and costly harm to many thousands of people, or to many more.

The other point I offer on trust is drawn from the abovementioned study, which states that leaders and managers are the fundamental enabler to grow trust. Additionally, the Commonwealth Counter-Terrorism Coordinator makes it clear that all leaders, in both the private and public sectors, have a key role in helping detect and mitigate extremism.

Whilst not all insider threat is about violent extremism – insider threat encompasses theft, fraud, data theft, insider trading, espionage, bullying, sabotage, and more – an insider threat program looks for aberrant behaviour which may indicate any of these behaviours and acts. Leaders need to decide to establish and maintain an insider threat program to mitigate the harms these acts would cause.

What about privacy and ‘rights’?

When talking to private sector entities about insider threat programs the response is often a series of questions about the legality of such a program, and assertions that unions and the workforce would not agree to it, and concerns that the operation of the program will infringe peoples’ privacy and rights. The mindset is that we can’t (or won’t) do this. I know that an effective insider threat program is achievable and can also explain why it is highly desirable.

An insider threat program is not focused on the person based on their particular attributes such as race, religion, psychological profile, sexual orientation, or other attributes. Instead, it is designed to detect aberrant behaviour, in relation to the workplace, requiring investigation and assessment to determine if the person may intend to, or already has, caused harm in the workplace. That harm may be to people, or operations, or to assets, or reputation. The harm will also be damaging to the insider themselves, so it is best prevented.

Australia’s Privacy Act 1988 provides protection to people in Australia and stipulates in Section 14 privacy rights known as the Australian Privacy Principles (APP), which govern standards, rights, and obligations around:

- the collection, use and disclosure of personal information

- an organisation or agency’s governance and accountability

- integrity and correction of personal information

- the rights of individuals to access their personal information.

The APPs are principles-based law. This gives an entity flexibility to tailor its personal information handling practices to its business models and the diverse needs of individuals. The APPs are also technology neutral, which allows them to adapt to changing technologies.

Let’s look briefly at rights and how they might apply in the contemporary workplace in the context of insider threat.

The Australian Parliamentary Education Office cites rights as follows.

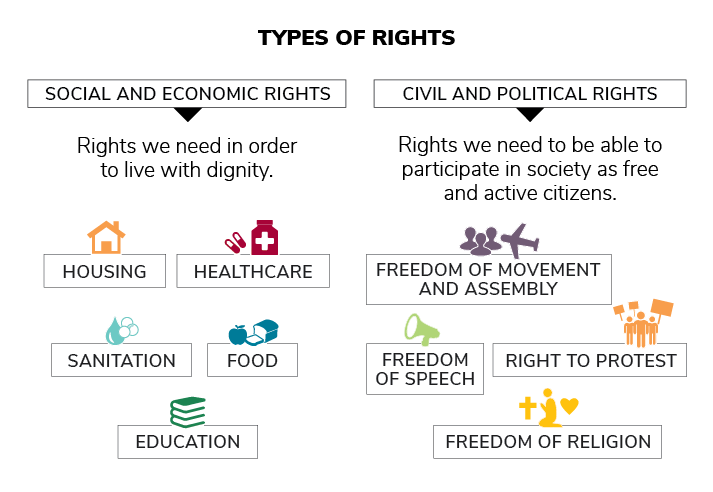

- A right is a moral or legal entitlement to have or be able to do something. Rights are created by laws.

- Rights can describe things that we should all be able to access, such as the right to housing, to healthcare, to sanitation, and to education. These rights are sometimes called social and economic rights because they describe what we need to have access to in order to live with dignity.

- Rights can also describe actions that we should be free to do without interference by the government or other groups. This includes the right to practice a religion, to meet in groups, to express our opinions and to protest. These rights are sometimes called civil and political rights because they describe what we need to be able to do to participate in society as free and active citizens.

- Human rights are rights that all people are entitled to, no matter who they are or where they live. They are protected by international law and include social and economic rights, and civil and political rights.

The Australian Parliamentary Education Office provides the following diagram to explain the matter of rights.

PARLIAMENTARY EDUCATION OFFICE (PEO.GOV.AU)

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) discussed the law and traditional rights and freedoms in its Traditional Rights and Freedoms-Encroachments By Commonwealth Laws (ALRC Report 129) in 2016, stating:

- 2.54 Laws that interfere with traditional rights and freedoms are sometimes considered necessary for many reasons—such as public order, national security, public health and safety. The mere fact of interference will rarely be sufficient ground for criticism.

- 2.55 Important rights often clash with each other, so some must necessarily give way, at least partly, to others. Freedom of movement, for example, does not give a person unlimited access to another person’s private property, and convicted murderers must generally lose their liberty, in part to protect the lives and liberties of others. Individual rights and freedoms will also sometimes clash with a broader public interest—such as public health or safety, or national security.

- 2.56 Accordingly, it is widely recognised that there are reasonable limits even to fundamental rights. Only a handful of rights—such as the right not to be tortured—are considered to be absolute. Limits on traditional rights are also recognised by the common law. In fact, some laws that limit traditional rights may be as traditional as the rights themselves. However, such laws are generally regarded as part of the scope of common law rights, rather than as limits or encroachments on those rights.

- 2.58 Nevertheless, much of the value of calling something a right will be lost if the right is too easily qualified or diluted.

The purpose of this brief exploration of rights and privacy in the Australian context is that people often assert rights, be they tangible or inferred. We have seen in many Western democracies in the 21st century an expansion of peoples’ willingness and preference to quickly assert a ‘rights’ defence to either gain a benefit or achieve an outcome they prefer, such as working from home in a post-COVID environment. This behaviour has some alignment to the trending focus on assertive DEI in recent decades.

However, very few rights can be considered absolute, and they are contextual. Arguably, this trending culture of asserting individual rights at the expense of entity or group rights contributes to workplace discord and personnel problems, including personnel security problems. This trend tends to increase the likelihood of insider threat because more people become disgruntled in the workplace because they see their ‘rights’ are not being respected.

The Critical Pathway to Insider Risk (Shaw & Sellers, 2015) is a psychology-derived framework used to understand and identify potential insider threats within an organisation. It analyses a progression of factors, including an individual’s personal predispositions, stressors they face, concerning behaviours they exhibit, problematic organisational responses, and ultimately, the potential for malicious actions. The framework essentially maps how an individual could move towards committing an insider threat act based on a combination of these elements.

The Critical Pathway has been adopted by Australia, the U.S. and the UK and informs the insider threat design of Australia’s national security and defence agencies. The Critical Pathway recognises that people are different from one another, they bring those differences to the workplace, and their innate psychological and experiences mean they may react in certain ways to drivers in the workplace and external to it through their employment.

Workforce screening: a core component of an insider threat program

An effective insider threat program is not only about detection and response but also about prevention. Workforce screening plays a fundamental role in mitigating the risk of insider threats before they manifest. This is especially crucial for entities operating in critical infrastructure, where the consequences of an insider threat can be severe.

The AS 4811:2022 Workforce Screening Standard sets the benchmark for managing human risk in high-stakes sectors such as energy, water, telecommunications, and transportation. It provides a structured approach to screening, ensuring that organisations implement robust vetting processes throughout the entire employee lifecycle—from pre-employment checks to ongoing assessments and secure offboarding.

To align workforce screening with insider threat mitigation, organisations should consider the following key principles:

- Legislative compliance – Screening processes must adhere to relevant laws and industry regulations, including the SOCI Act, the Privacy Act 1988, and other employment and anti-discrimination laws.

- Privacy and informed consent – Candidates must provide informed consent before screening is conducted. This consent should not be enduring but rather sought at different stages of employment where further screening is necessary.

- Transparency in recruitment – job advertisements should be upfront about the screening process, making it clear that compliance with workforce screening is a condition of employment.

- Confidentiality and organisational probity – Candidates should be required to accept confidentiality requirements, ensuring they understand their duty to safeguard sensitive information.

- Continuous screening and monitoring – Workforce screening is not a one-time process; it should be integrated into the employment lifecycle to detect changes in behaviour, external influences, or new risk factors.

- Communication strategy – Organisations must effectively communicate the rationale behind workforce screening to employees and stakeholders. The screening process should be framed as a protective measure rather than an intrusive process.

Insider threats often arise from employees who have undergone a shift in behaviour, ideology, or loyalty. However, many insider threat cases can be prevented if the right workforce screening measures are in place. A well-designed screening framework helps ensure that only individuals with the right credentials, values, and security mindset are placed in positions of trust.

By integrating workforce screening into an insider threat program, organisations create a proactive defence mechanism, ensuring they are not only reacting to threats but actively preventing them.

What is the nexus between changes wrought by the U.S. government, contemporary DEI issues, the Australian workplace, legal rights, and increasing demand for insider threat programs?

To recap, in the first part of this article I set out the recognition by the Australian Government that we need to focus on the insider threat – understanding what it is and that it needs to be actively mitigated.

In the second part, I spoke about Australia’s recent action on insider threat and the reality of insider threat for Australia today. Next, we considered legal and implied rights and how the trend to increasing individualism being asserted over group wellbeing can lead to workplace problems.

How does all this connect in the Australian context?

Australia, like the U.S. and the UK, has experienced significant social and economic disruption from 2020 onwards due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its legacy. In addition, the roiling relations between the U.S., the West, and China and Russia have generated great uncertainty and increased risk of military conflict. There has also been military conflict, with war in the Middle East and in Ukraine, which is the largest war in Europe since 1945. In Australia, these events have produced a cocktail of drivers that shape behaviour which people carry into the workplace.

The drivers include:

- Tough economic times making people desperate and disgruntled.

- War in the Middle East has been the catalyst for increasing protest and violence based on race and religion.

- Adversary nations have recruited or co-opted Australians to conduct espionage and foreign interference.

- Workplace laws have further strained employer-employee relations.

- The move to ‘turn the dial down’ on the promotion of DEI causes will cause social friction that spills into the workplace.

- A mentality of victimhood (stemming in part from the DEI movement) has arguable taken hold in parts of the community presenting challenges to cohesion and security in the workplace.

All these, and more, will play out in Australia’s workplaces today.

In the case of critical infrastructure entities, the government has made it clear through the SOCI legislation that owners and operators– the leaders – of these assets need to, and are in fact obliged to, put an effective insider threat program in place.

The nexus between changes wrought by the U.S. government, contemporary DEI issues, the Australian workplace, and legal rights is recognition of the need for insider threat programs because people are core to Australia’s success and security. In Australia today many people are vulnerable and so may behave in the workplace in a harmful way. People need the support of their leaders.

People, as trusted insiders, can present as a threat to any entity. Not all insider threats have the same consequence – a person stealing a company laptop is not as consequential as nurses claiming they will kill people or as a person passing on secret submarine information to an adversary nation, rendering a submarine vulnerable to attack – but they all share the same pathology of a person abusing the trust invested in them to cause harm to the entity that trusted them in the workplace.

Leaders and managers across the government and private sectors have been told that insider threat is real, is relevant, and needs to be addressed by them. The naysayers will seek to stop insider threat programs by claiming that such programs impinge on their rights and privacy, but a well-designed insider threat program will not.

It will rebalance the workplace cultural pendulum back from a DEI-generated extreme towards the centre where both employees and employer may all benefit and the security of the entity can be maintained.

An insider threat program is a protection for everyone, detecting and stopping harms to people while also preventing trusted insiders from inflicting harm on themselves.

If enough individuals in an organisation have sufficient knowledge, skill, and – most importantly – a personally felt commitment to protect the safety, security, and well-being of their colleagues and organisation, even limited insider threat policies will succeed!

In closing, I say that the nexus between changes wrought by the U.S. government, contemporary DEI issues, the Australian workplace, legal rights, and increasing demand for insider threat programs by government can be seen as a compendium of an array of diverse security drivers confronting Australia. As put by the Director-General of ASIO in February 2025: “Australia is facing multifaceted, merging, intersecting, concurrent and cascading threats. Major geopolitical, economic, social and security challenges of the 1930s, 70s and 90s have converged.”

I see DG ASIO’s assessment making clear that Australia is facing unprecedented threats to our social cohesion and national security. All these drivers are affecting the people in your workplace. Your employees and suppliers are both an asset and a threat but can and should be treated with respect and within the law. However, that approach does not mean employees enjoy a lop-sided bargain in the workplace. Where an employer extends trust there is an agreement which sees that trust being reciprocated by the employee. An insider threat program helps verify that trust is intact.

An effective insider threat program is the nexus of available information which affords visibility of threats and contains the tools to act in order to maintain the security of assets and operations which in turn bolsters Australia’s national security.

[1] Paul J, Zak, The Neuroscience of Trust: Management behaviours that foster employee engagement, Harvard Business Review, January-February 2017 pages 84-90.